Even with the dominance of digital and streaming, the physical format remains strong. This is because the physical copy still gives the player a clear sense of ownership. The feeling that the company can't take the game away from you. The game is yours!

The physical format also helps those who like to have better control over where their money is going. When you buy a game on disc or cartridge, it's right there in your hand; there's no subscription, no license that can change later, no risk of it disappearing without notice.

You buy the game, put it on the shelf, lend it, resell it, trade it, do whatever you want. This doesn't exist in the digital world, where everything depends on the store, the platform, the terms of service, and server availability. If Steam disappears tomorrow, all your games will go with it.

This more practical and emotional side has always existed, since the first consoles. Gamer culture was born revolving around boxes, manuals, and freebies. Physical games are born from this tradition and still carry part of it. Even today, when covers are simpler and manuals have disappeared, there's enormous symbolic value in having the game as a real object. And this relationship isn't just nostalgia: there are very concrete factors involved.

From the cartridge era to optical media

In the beginning, all consoles used cartridges. Atari, Nintendo, and several other consoles worked that way. The "cartridges" were durable, fast, and almost never had reading problems (blowing would fix it). The downside was that the technology was limited and much more expensive to produce. Nowadays, it's easy to make a complete, beautiful Master System game and show how much more the console's processor could do than what they delivered at the time. But putting that on a cartridge of, at most, 8 bits is another story.

Still, it was the standard. This lasted until the mid-90s, when PlayStation 1, Sega Saturn, and other consoles switched to CDs—then DVDs and later Blu-rays. It was a significant turning point because discs were cheap, had much more storage space, and allowed games to grow in size without significantly increasing production costs.

The migration to discs established a new standard in the market, but it didn't completely kill the idea of robust physical media. Over time, developers realized that increasingly larger games were hitting the speed and capacity limits of traditional optical media.

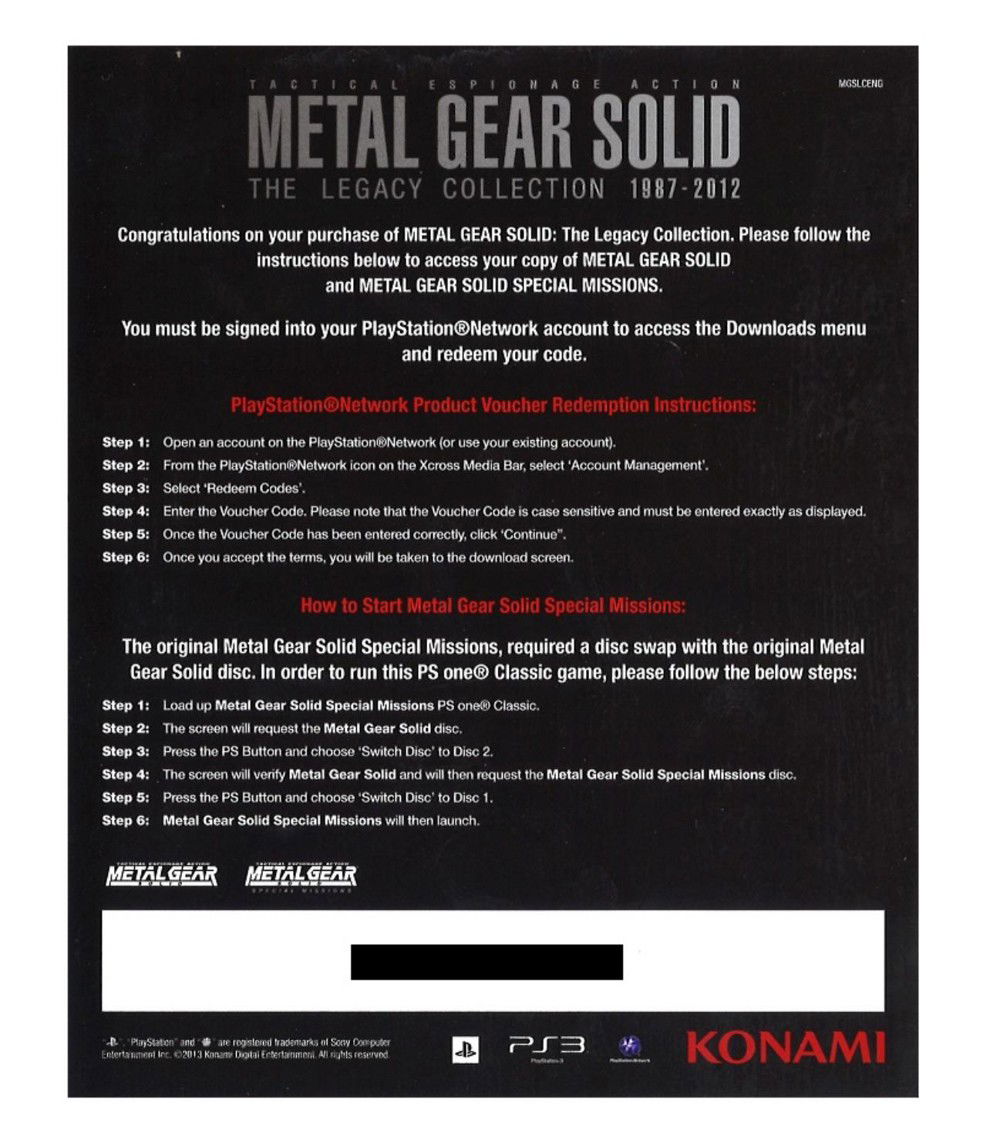

And this transition also changed the physical "package." Huge manuals began to disappear, boxes became simpler, and ultimately, the disc became the main element. In many current releases, especially on PS5, you open the box and only find the disc—and sometimes not even that, since some versions only come with a download code. This would pave the way for something many people didn't expect: the return of cartridges. Not exactly as before, but they would return.

The return of cartridges and current production

With the evolution of flash memory, modern cartridges have become small, fast, durable, and cheap enough to compete with discs. This was one of the reasons that led the Nintendo Switch to adopt game cards. They load games almost instantly, don't have the problem of wear and tear from optical reading, and are very practical. This restored some advantages to physical media that had disappeared in the early 2000s.

Meanwhile, discs continue to exist, but face real challenges. Sony, for example, announced the end of Blu-ray media production, which directly affects what happens to physical games from now on. There are rumors that Nintendo's next console will still use cartridges. In the case of Sony and Microsoft, the trend points to an increasingly digital scenario, but still with room for physical media, especially for collectors.

This mix of formats—modern cartridges on one side, discs losing ground on the other—shows that physical media hasn't disappeared. It has only changed its function. Today it’s both an efficient form of distribution and an item that speaks to the player's emotional memory.

The problem of "always online": the case of The Crew

One of the strongest points keeping physical media alive is precisely the fear of digital dependency. Games that need to be connected all the time create an absurd situation: even those who buy the disc end up depending on the server. When it's shut down, it's over. Ubisoft demonstrated this very clearly with The Crew, released in 2014. In 2024, when the servers were shut down, the game simply stopped working, even for those who had a physical copy. There was no offline mode.

Ubisoft's response, director Philippe Tremblay told Game Industry Biz for this case, and for others in the future: "The player must get used to the idea that the game isn’t theirs."

Game streaming services, such as Steam and Epic, are increasingly displaying warnings that players are purchasing a "Game Usage License" and not the game itself. GOG remains firm in its policy of selling the game and not just licenses.

The fan reaction was strong. In the United States, a lawsuit accuses Ubisoft of selling something that wasn't actually the game, but only a temporary license. The discussion revolves around the idea that if physical media doesn't guarantee access to the content, then the consumer has been deceived. Other games shut down in the past—such as Assassin's Creed 2 and 3, or Knockout City—at least had some offline mode. The Crew, however, became a dead item.

But the community didn't take it lying down. The project The Crew Unlimited emerged, attempting to recreate servers on its own to keep the game alive. It's a preservation attempt made by the players, not the company responsible.

This case became a symbol of how fragile the digital world can be and how the physical world still serves as the only way to guarantee that something doesn't disappear overnight. Even if a game depends on servers, the disc at least tries to preserve part of that content, while the digital version vanishes without a trace.

Tangible advantages of physical media

Beyond the emotional weight and technical aspects, there's the commercial side. Many people believe that digital is cheaper because it cuts production and distribution costs, but this hasn't been confirmed in practice. Digital prices take much longer to fall, while physical prices plummet during promotions, sales, and used goods stores. Buying a physical game and reselling it later reduces the final cost for the consumer, making the price fairer.

With digital, you can't resell, lend, or trade. It's a purchase "locked" in your account and the store's rules. With physical, you can do whatever you want. This creates a kind of freedom that digital doesn't yet offer (and that many companies, like Sony and Microsoft, don't want you to have).

Collectors know this well. Shelves serve as a record of the player's personal history, something that digital doesn't replicate. Those who like to have control over their things see physical as a guarantee.

And this isn't just a whim. It works as an escape from digital stores, which have increasingly more control over prices and availability. Physical media reduces this burden and gives the player a minimum of autonomy.

Special editions and the collectible appeal

Companies know this attachment exists, so they invest in special editions. These are huge boxes with figurines, artbooks, soundtracks, and all sorts of items that directly appeal to dedicated fans. They aren't cheap, but they work because they transform the game into an object. The logic is similar to vinyl collecting: it's not just about the content, but about the piece itself.

The physical market tends to shrink, but it should continue in this premium direction. Old cartridge games, for example, have already become collector's items, as have re-releases of classics in limited editions. It's an active market in the whole world. Movements like “Stop Killing Games” have gained strength precisely because of this: players who want preservation and respect for the cultural value of these products.

Physical media has become a way to keep part of video game history alive. As digital media grows, the value of something tangible intensifies. And as long as this emotional and historical connection exists, special editions and collectible items will continue to attract an audience.

However, there are also parallel markets for physical copies of fan games being sold separately. This is the case with the Mega Drive port of Real Bout Fatal Fury Special by RheoGamer. The problem was clear: the developer confirmed that third parties began producing and selling cartridges of the project without permission. Users of AtariAge reported that the company Retro X sold these cartridges at events and online, contradicting the fact that the ROM was only distributed for testing.

This unauthorized sale ultimately weighed on the decision to cancel the project, as the author didn’t want to see a fan game being commercially exploited before it was even finished—and much less without any license from SNK. The episode became a clear example of how retro collecting can run into copyright conflicts, bad faith, and misappropriation of fans' work. This illegal sale caused the developer to abandon the project and cancel the port completely.

Future prospects and conclusion

Today, physical editions persist for several reasons: security against server shutdowns, resale possibilities, more flexible pricing, collectible appeal, ownership control, and cultural resistance. All of this sustains the format even with a market increasingly focused on digital distribution.

Analysts predict that physical copies will continue to be released at least until the end of the decade, even if on a smaller scale. The trend is for them to become increasingly geared towards collectors, with special editions and more elaborate extras. This is not a farewell, but a transformation. The physical no longer competes directly with the digital—it occupies a different space. A space that mixes history, affection, and the desire to have something concrete to call your own.

Physical media remains relevant because gamers value what they can hold, keep, and preserve. In a world where more and more things become services, subscriptions, or temporary licenses, having the game on the shelf still means something. And as long as it does, this format won’t disappear.

— 评论 0

, 反应 1

成为第一个发表评论的人