There has always been a feeling that The Game Awards sought to embrace two polarities: that of billion-dollar blockbusters that shape trends and that of medium- and small-sized studios that, even without equivalent resources, manage to redefine the creative landscape.

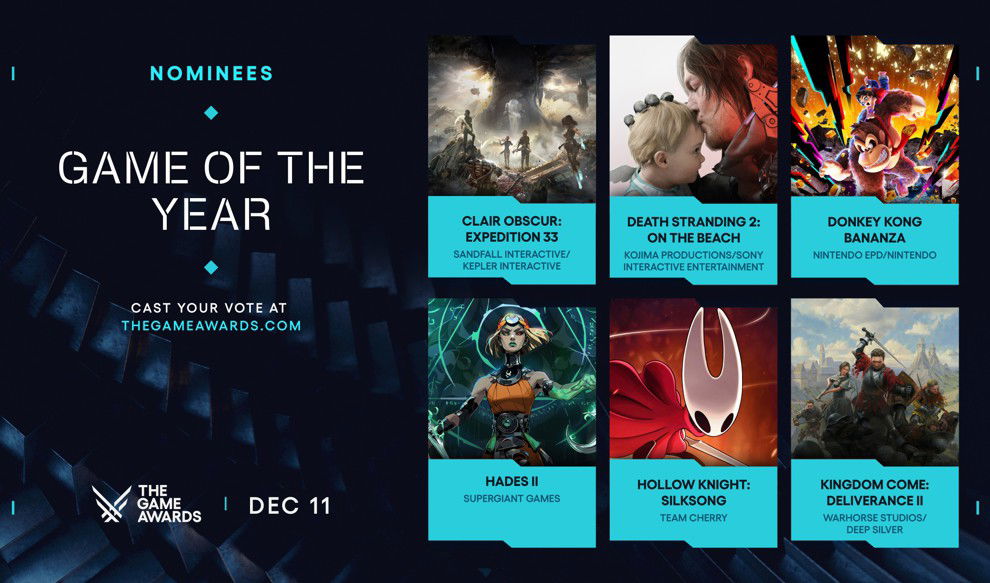

This year, however, before the ceremony took place, the list of nominees for Game of the Year served as a kind of silent message of where the public is moving or, at least, where it intends to look from now on.

The presence of titles like Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, Hades II, and Hollow Knight: Silksong among the year's top contenders may reflect, in addition to recognition of their inherent qualities, the winds of change that began slowly, gained momentum throughout the last generation—driven by limitations, uncertainties, and post-pandemic reinventions—and are now materializing more clearly: creative genius is, once again, asserting its place in the gaming universe.

The public, especially from single-player titles, seems to be moving away from the almost full dependence on large blockbusters, driven by the expansion of cinematic and gigantic open worlds, and allowing themselves to seek more compact, direct experiences focused on ideas.

Their focus has shifted to games that don't demand the world to deliver something memorable, nor do they rely on the promise of ultra-realistic graphics or gigantic marketing campaigns to deliver something unforgettable. Games that, in the end, return to the original purpose of video games: to offer something fun, well-structured, creative, and innovative.

We cannot confuse these elements with an abandonment of AAA titles, which remain at the core of the industry; it's more akin to an inflection point or redirecting expectations. This year's nominees clearly show that it's not that blockbusters have lost ground; they just aren't, at least in 2025, at the epicenter of the agenda.

The Game Awards 2025, consciously or not, sends a message even before its announcements: what defines "great" in a video game is changing and, above all, who decides that is changing.

The Clair Obscur, Hades II, and Hollow Knight: Silksong Factor

When Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 emerged, the game attracted attention for its blend of surrealist aesthetics, turn-based RPG combat focused on a rhythmic, almost dance-like system, and a narrative approach that highlighted the game's strong voice-acting cast. Initially, the title generated hype for being unconventional while seeming eerily familiar to RPG fans.

The Sandfall Interactive title, produced by a smaller team than any blockbuster and yet with impeccable quality, didn't seem to want to compete for the same space as AAA titles: Clair Obscur seemed auteur-driven, compact, and very focused on its own ambition.

What nobody imagined is that this uniqueness would end up capturing the attention of so many people — critics, the public, and now, on the biggest awards stage in the industry. The game has already received the Game of the Year title at the Golden Joystick Awards and has also won awards in other categories, and no matter what media outlet questions it, the collective perception is that it is the clear favorite to take home the statuette at The Game Awards.

Hades II reinforces the perception of a change in perspective from another angle. The first Hades was widely acclaimed, and its sequel continues to carry the mentality of the first title: careful production, focus on mechanics, outstanding artistic style, and a narrative construction that uses the roguelike as immersion.

It appears among the nominees because it continues to bet on density in what it offers best: characters, style, and everything in between.

Hollow Knight: Silksong occupies symbolic territory. The sequel to one of the most celebrated indie films of the decade, and almost with a shadowdrop, manages the feat of being among the major contenders even after years of waiting, delays, and silence.

Silksong exists and is consecrated through the confidence built by the previous work. The public believed in Team Cherry's vision, in what the game represented, and that the experience upon release would be worthy of the title—and received something that lived up to expectations for most, even reigniting debates about the fine lines between fun and difficulty in games.

The prominence of these three this year represents a growing willingness among the public to value works that prioritize ideas over budget. These are games that don't try to simulate cinema, much less rival gigantic open worlds in an attempt to showcase technological marvels. They are games made by people who love games and, above all, they are interesting games.

The fatigue of “bigger, more realistic, more cinematic”

For much of the last decade, there has been an increasing inclination in the industry to pursue maximum scale, the most realistic image possible, and a narrative as close as possible to a big-budget film. This trend produced remarkable works—Skyrim, God of War, The Last of Us I & II, Cyberpunk 2077, The Witcher 3, and a dozen other titles that marked generations—but it also created absurd pressure on studios, teams, and consumers.

Games began to take more years to develop, budgets skyrocketed, and the line between “game” and “Hollywood-like entertainment product” became more blurred; it was almost a race where everything needed to be epic, monumental, and, above all, cinematic.

The inevitable consequence of this movement was weariness. The public began to feel that many of these big games were, paradoxically, too similar—immense open worlds, full of markers, with similar narrative structures and ambitions driven by engagement metrics. Meanwhile, smaller productions began to gain more visibility by offering fresh experiences.

There is a consensus among enthusiasts that every game takes a formula that worked and replicates it until it falls into fatigue. Take The Last of Us as an example: many have used the same tropes, whether in the zombie apocalypse aesthetic (Days Gone) or in the narrative of "tough guy trying to protect a younger figure" (God of War / God of War: Ragnarok).

It's not as if these games are all the same, but they saw something that worked there and tried to replicate it, creating their "own version of it," like a mold or a formula to follow to create a new variant of that narrative—and it's far from the first time: how many "main characters with giant swords and/or spiky hair" appeared in games after the release of Final Fantasy VII in 1997, back in the PSOne/PlayStation 2 era?

The success of AA and successful indie games has created a possible counterpoint of exchanging the expansive and ultra-realistic world for "more focused" experiences that don't try to be everything at once, but choose a path—be it mechanics, aesthetics, or idea—and work on it to the very end.

By doing so, they end up offering something that many Triple-A games already have difficulty achieving due to high budgets, expanded team sizes, increasingly tight deadlines, and progressively more surreal expectations: identity.

The public hasn't turned against big games, but their relationship with them seems to be changing. Consumers will always question what they want from a game: between gigantic maps and extreme realism or unique mechanics and art direction with stories capable of surprising and breaking away from pre-established formulas, because trying to have everything at once doesn't add up for most titles.

The massive nomination of AA and independent games for the top prize at TGA 2025 suggests that the pendulum is swinging again, and where before people sought the most realistic graphics, today they seek something closer to passion, something that reminds them why they like video games.

The AAA games are still here and aren't going anywhere

That said, the list of nominees also reinforces that the industry hasn't abandoned its giants, and the public doesn't intend to do so anytime soon. Kingdom Come: Deliverance II and Death Stranding 2 are solid proof that the space for large-scale games remains guaranteed, as long as these projects find ways to stay relevant and build their own formulas.

Kingdom Come: Deliverance II is extensive, detailed, historically meticulous, and yet adopts a more controlled scale than other blockbusters. It is undeniably an industry giant, but it relies on authenticity and speaks to an audience that seeks immersion and coherence above other aspects.

Death Stranding 2 carries a more experimental and ambitiously auteur-driven scope, unlike anything other major studios would be willing to finance, typical of Hideo Kojima. It relies on what makes it unique, taking the risks of not succumbing too much to the demands of those who labeled the first title in the series a "delivery game".

The looming shadow of GTA VI

Above the trends, nominees for The Game Awards, or debates, looms the shadow of GTA VI, the most anticipated game of the decade, perhaps the most anticipated of all time. It's impossible to discuss changes in the relationship between the public and the industry without considering the impact that Rockstar's next title will have when it hits stores, possibly in November 2026.

Rockstar's ability to transform trends into new norms is unparalleled. Just remember that GTA V influenced everything from open-world games to online systems and even expectations about a title's longevity, and even without a release this year, GTA VI was the talk of the town.

The mere anticipation for it shaped release dates, fueled theories, and kept the market attentive to Rockstar's every move. GTA VI could, on its own, redefine technical, narrative, mechanical, and marketing standards in games—and, in doing so, reorganize the industry's axis once again.

Therefore, although 2025 seems to indicate a greater inclination towards more compact experiences, it's impossible to ignore that the release of GTA VI could turn the tables for the largest open world of all time, presenting a new path that often becomes a benchmark: every game will be compared to GTA VI, and every title may eventually succumb because it wasn't as incredible as GTA VI.

Faced with this Triple-A colossus poised to shake the entire industry, it's up to developers and consumers to define which route will be best to follow.

Perhaps the message of the year is the need for more plural titles: to abandon the concept of a dominant model and accept video games as a medium of non-linear changes, allowing small studios to influence the medium's language, and for the rise of compact works in future generations to allow independent projects to coexist with monumental blockbusters.

This year brought back the feeling that gamers have options that don't depend on scale, budget, or trends, and it would be good to foster this path as an invitation to balance instead of using it only as an anecdotal attack on AAA titles.

It's a reminder that grandiose games aren't the only ones capable of carrying the market, that smaller productions deserve space as an essential part of the ecosystem, and that AA titles, like Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, become a reference that it's not necessary to invest a huge budget in pursuit of glory: it's enough to let passion, that amorphous tool that unites us around the same medium, be an important factor in the direction games can take.

The Game Awards may not have consciously intended to send this message, but the list of nominees did so on its own. The strength of video games lies in creativity, and amidst the exhaustion with so many similar titles and a feeling of fatigue with every discussion surrounding games that involves a sign of late capitalism, perhaps the gaming public is finally turning the spotlight back on what a game truly means.

Thanks for reading!

— Comments 0

, Reactions 1

Be the first to comment