Between an Empire and Roses

This story begins like this: an ambitious emperor obtains magical powers, capable of bringing demons from Hell to the world, and uses them to begin the campaign of conquest and expansion of his empire, Palamecia, taking village after village and kingdom after kingdom.

Eventually, their crusade reaches Fynn, who starts a resistance force known as Wild Rose. Despite their efforts, an unexpected betrayal causes Fynn to succumb to the empire and be annexed as part of its territory.

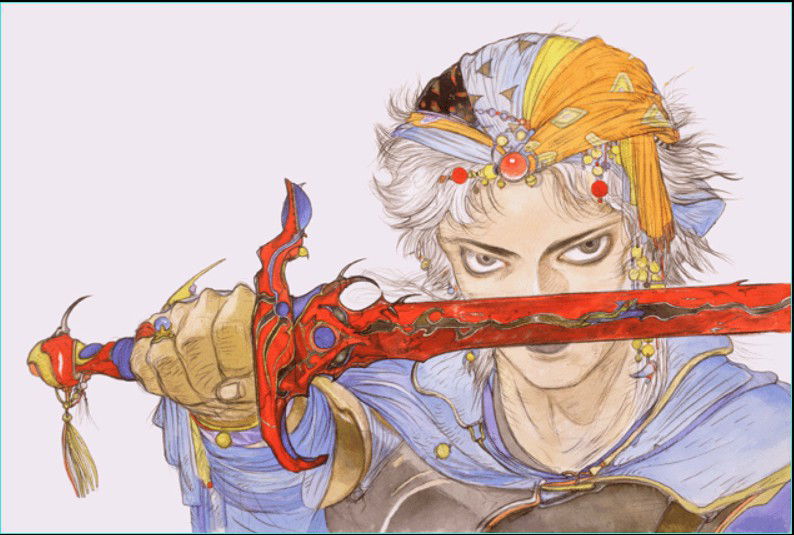

Among the refugees are four young warriors who lost their families and homes to the Empire. Shot down in their escape by the fearful black knights, these young men are rescued by Wild Rose, beginning the series of events that will take the life of this Emperor and lead his own empire to ruin.

The narrative above refers to one of the most famous fiction and youth literature premises in the world, reproduced in various works, with Star Wars being the most famous of them in 1988, five years after Return of the Jedi and, also, the year of release of Final Fantasy II.

The sequel to the first Final Fantasy features a distinct and innovative premise in many ways when compared to its predecessor, experimenting in ways no other game in the franchise has attempted, making it one of the black sheep of the franchise, with polarized reviews among those who love and those who hate it.

Four Warriors, No Prophecy

In my review of the first Final Fantasy, I explained how the game's success was consolidated under the premise of using already established elements of the tabletop RPG to create a work with its own narrative, while evoking belonging for those looking for a “Dungeons & Dragons experience in an electronic RPG”, in addition to presenting and consolidating permanent elements of the franchise.

Final Fantasy II consolidates other pillars for the series, with the two most striking and present from its first minute: innovation and story.

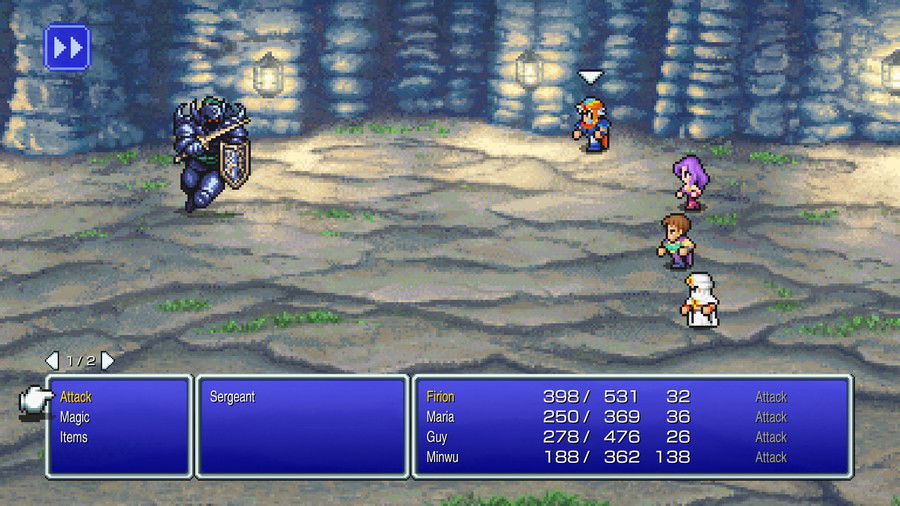

The game begins with the four heroes fleeing from the Empire's cavalry and quickly defeated by them - yes, the first impression of the title is that your characters are too weak to escape, fight and much less face their oppressors; their survival in Fynn is no more than a force of chance or, perhaps, destiny.

This beginning is a radical change compared to Final Fantasy, where the four playable characters are considered the last hope of a decadent world, predestined to an adventure to bring light and balance back - a premise which offers a huge sense of power to the player.

Destiny is a dubious message in the second game, mentioned only by the healer Minwu in one of his first dialogues with the heroes. Firion, Maria, Guy and Leon are survivors of a land devastated by war and the machinations of a megalomaniac emperor, whose only desire is to join the bastion of resistance against his tyranny.

This new structure is the milestone that differentiates this game so much from its predecessor and sets the precedent for a point where the series stands out in each title, the ability to change everything: the crystals do not exist, there are no prophecies, the Jobs were abolished, and even character leveling was restructured to reward players for what they do in each battle - Almost everything that Final Fantasy built in its first game was redesigned in its successor.

Building the New Pillars

Recreating the mechanics from scratch means a step-by-step trial and error. Final Fantasy II presents more mistakes than successes in its structure, but the elements in which it managed to build and improve have become some of the most solid pillars of which support the series to this day, including its recurring elements.

The main and best known of these are the Chocobos, introduced as a means of quick transport to avoid battles when traveling long distances on land. They later became one of the most iconic figures in the series, present in every title since then.

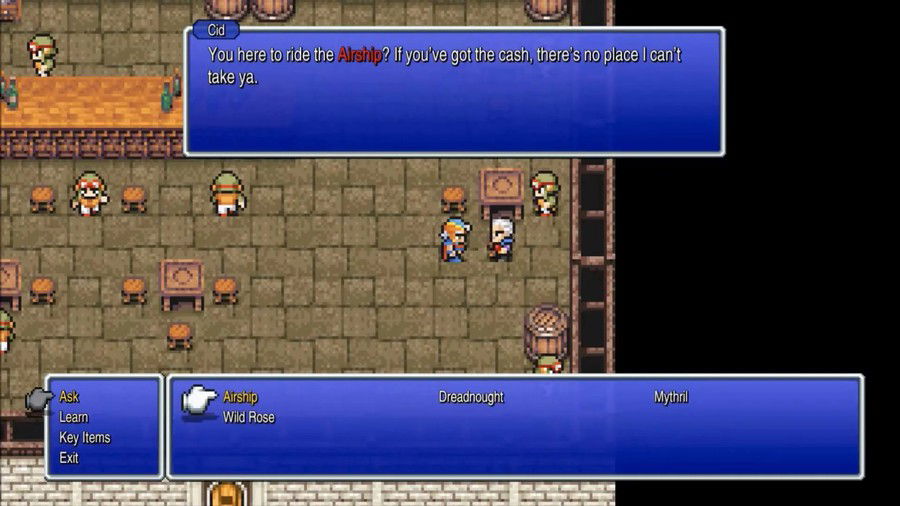

Cid has also become another mainstay, and in addition to introducing him as a character, Final Fantasy II also begins the tradition of associating him with airships and having great knowledge of how they work - a key element for this game's story.

The magic Ultima, commonly the strongest of the games where it is present, also made its first appearance in FFII with a significant role in the story - a curious fact is that it was bugged in the original NES version, making it much worse than other high-level spells, such as Holy and Flare.

The first appearance of a Dark Knight was also in Final Fantasy II, as a key character in the plot and an important ally of the Emperor. Its availability as a job and playable character would only happen in the following game. In addition to him, Guest party members were also introduced in this game.

Despite having no physical appearance, this is also Leviathan's first appearance in the series, as the guardian of the Mysidia Tower. This correlation between the colossal creature and Mysidia will also be the central focus of Final Fantasy XVI's next expansion, The Rising Tide.

The First History-Driven Final Fantasy

In the first game, Final Fantasy sought to exude familiarity with tabletop RPGs as its main attraction. In the Warriors of Light and their adventures, the characters and regions serve as an auxiliary line to guide the player through a series of quests until the end of the journey.

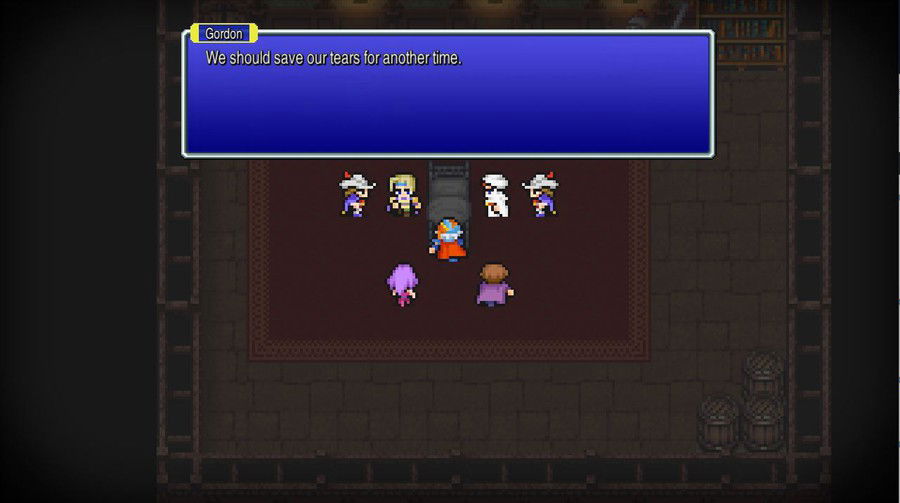

Final Fantasy II's biggest innovation is in giving up the sense of adventure and “D&D structure” in favor of its coherent story and narrative-driven gameplay, with active participation of secondary and tertiary characters in the plot, as well as a villain whose atrocities are the core of its development and adds a constant sense of urgency to the game.

Its story is quite dark for the time, and its surroundings make it heavier than its successors until Final Fantasy VI. Both, by the way, have empires seeking world domination through force in the role of major antagonist.

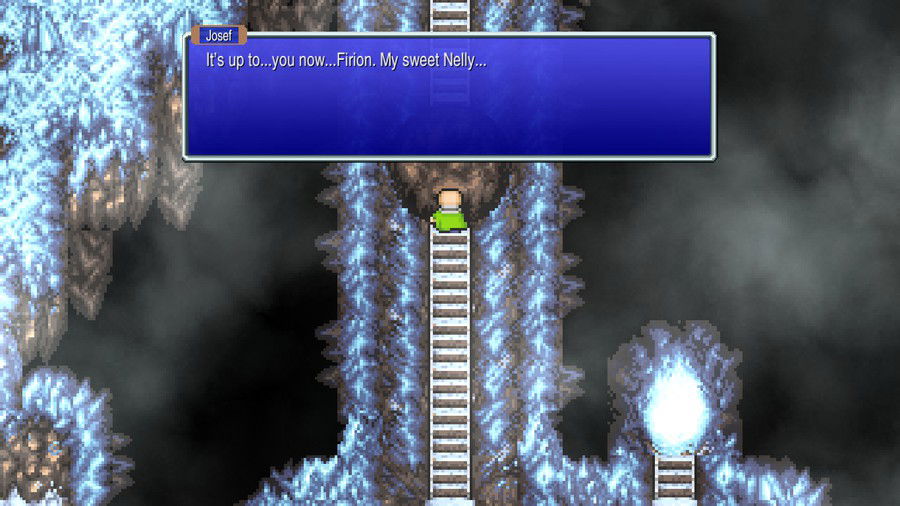

In it, playable characters die or sacrifice themselves, cities are bombed and destroyed, nations are decimated and there is no shortage of dialogues where NPCs explain how the Emperor's actions affect their lives and bring the same feeling as the first combat: that of Firion and his allies facing an foe who is much more powerful than them.

This feeling is part of Final Fantasy II's charm and applies elsewhere. Its story is not incredible or exceptional and despite its good quality for the time, it stumbles on factors inherent to the limitations in which it was released and the conception of what a video game adventure should be in 1988.

Its narrative is cliché, it was designed this way by sharing several common key elements about empires and their fall at the hands of a resistance group in other works, and it suffers a lot from its unfocused execution, which prevents creating emotional impact even when a character sacrifices themselves to help the heroes because not even they seem to care too much about it, and most of their dialogues don't make them very memorable.

Even with notorious execution problems by contemporary standards, the introduction of a story in Final Fantasy II and the transformation of gameplay around actively participating in the unfolding of a war was the game's greatest hit and its legacy for the franchise - the series today is known for the quality of its narrative in worlds with remarkable characters, and none of this would be possible if Hironobu Sakaguchi and his team weren't ambitious enough to cross the lines that the first game established to try to experiment with new formulas.

The Ambition which Caused Stumbles

But the ambition to innovate and try new formulas while moving away from the ones which worked in the first game also brings failures, mistakes and disappointments. While creating a narrative and using it to guide the player was accurate, this game stumbled at other points by not following part of what worked with Final Fantasy.

Among them, the most famous and guilty of turning people away from FFII is its progression system, but other aspects, such as the use of passwords and its dungeon design, were and still are criticized as low points of the game.

The Unique Progression System

Final Fantasy II foregoes the famous character progression through levels to introduce an innovative progression system which rewards characters for what they do in battles.

Attributes such as HP and MP and your proficiency with weapons and spells increase based on each character's actions during combat - for example, if a character takes enough damage in a battle, they will gain HP and may gain Stamina upon emerging victorious, and if they use spells, they can gain MP and magic power.

They can gain evasion bonuses if they are targeted by attacks, and they gain strength if they attack frequently. Following this same logic, spells evolve and gain “levels” as they are used, becoming stronger and more comprehensive in their effects.

In theory, this method motivates players to use different ways to win battles, diversifying spells, weapons and other methods to ensure an efficient and flexible team to fight bosses and pass through dungeons.

In practice, it punishes players for following formulas and turns FFII into a grindfest, where it is necessary to spend more time in each battle to diversify actions and receive increases in each character's most important attributes.

Furthermore, this attempt to motivate players to do a little of everything in each battle hinders the natural progress of the game and the characters themselves, being the biggest pillar of Final Fantasy II's difficulty.: A poor planning at the beginning can turn into a snowball as the story progresses, whether due to having too weak spells, irrelevant physical attacks, or too low HP and resistance to survive a more powerful boss or enemy.

This system also presents problems in the opposite direction: once understood, the progression system in Final Fantasy II becomes easy to break if you dedicate yourself to creating specific builds for each character, or exploring mechanics.

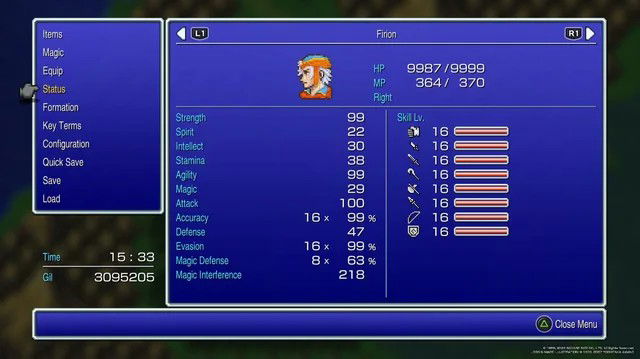

For example, in my campaign for this review in the Pixel Remaster version, I focused my characters on specific weapons for each one, giving up the use of shields to cause more damage and resorting to magic only for healing and dealing with larger groups of enemies, where its use would be rewarded - after five or six hours of campaign, my team was already dealing enough damage to eliminate any common enemy with one attack and taking two or three rounds to defeat bosses, in addition to having a high amount of HP and MP.

In other words, finding the middle ground in character progression in Final Fantasy II is the most complicated task in the game. If we don't understand how it works, we will be punished for being too weak and leaving too many gaps in our planning. If we understand and explore its leveling system properly, the characters are likely to become too strong in a short time.

The idea behind this progression is interesting, it became the game's biggest differentiator in the series, perhaps the main reason to give it a chance, but its execution is confusing without prior research and becomes easy to break once understood, losing its main purpose: to motivate different methods of winning in each battle.

The first with absolute character customization

Final Fantasy II also innovates and stands out in the character customization, where it moves away from the job system as a means of defining your team to require time and dedication to transform the characters in the way each player desires.

If you want a party of warriors with a lot of HP and strength, just focus on physical attacks and taking damage. If a character seems more interesting with a spear instead of a sword, change their weapon and fight enemies for a while to have a lancer ready.

If you prefer a party of mages, simply dedicate the equipment and resources to use more spells for longer, and you will soon have a group ready to defeat most enemies with no difficulty.

This absolute customization makes this game much more profitable in the long term than its predecessor, allowing an infinite number of different builds to complete the campaign, and paved the way for similar proposals in Final Fantasy XII, with the License Board.

The Confusing Password System

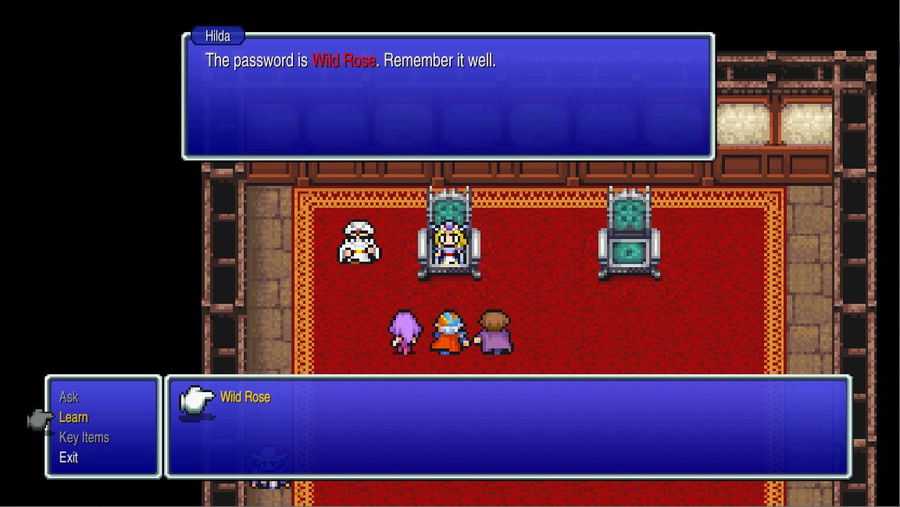

If combat divides opinions and opens up a multitude of possibilities when understood and played accordingly, the same cannot be said for the password system.

From the first minute, players can learn passwords and use key items from their inventory to interact with other NPCs. Both are necessary to progress the story and even unlock some secrets, but they are never intuitive.

Except for some obvious situations, passwords in Final Fantasy II generate few interactions, and force us to look for the right characters to interact with using them while not always giving us a clue on where to find them.

This resource would be best used If the game had its own structure of side quests, as in the brief interaction to get one of the strongest swords in the game, but in their absence, passwords become unintuitive for its time and even worse in 2024.

The Lack of Direction Persists

A notable problem in this game's design is its lack of direction: like its predecessor, Final Fantasy II rarely gives you any indication of what to do or where to find your next objective, forcing you to spend a lot of time going around the world at the risk of finding strong enemies and be greeted with a Game Over screen.

This problem repeats itself all the time, with rare moments where the game gives directly tells what the next step is to take - it is necessary to guess or explore dialogues with NPCs to discover your next destination and where to find it.

Frustrating dungeon design

The dungeon design is another negative point and the main element where Final Fantasy II suffers a downgrade compared to its predecessor.

Except for the last sequence of them, most of the dungeons are very similar and have the same pattern of “scattered treasures and doors that lead to empty rooms”, with an excess of empty rooms, with literal rows of four or five of them for the player to enter until they discover which one leads to the next floor.

If that wasn't enough, these rooms are known as Trap Rooms. The idea behind them is that, when taking a step in it, the player faces a group of enemies.

Since Firion is placed in the center of these rooms, it takes at least two battles to get out of it. Repeat this process three times in a sequence of four doors, and we soon have a very frustrating sequence until the team is strong enough to face this challenge.

This pattern makes exploration a tiring and unrewarding experience whenever we deviate from the path only to be stuck in the middle of an empty room, or when we go to a chest just to find a potion.

But it is not just evil that the deviations from the path in Final Fantasy II are composed of, and in addition to the challenge as significant or even greater than its predecessor for the dungeons, the game has more treasures with powerful hidden enemies and even secret walls, with most of them offering an excellent reward for investing your time searching for new secrets.

A Distinctive Experience

In essence, like other games of its time, Final Fantasy II is about grinding, and seeks to make it less repetitive and more rewarding by motivating the use of different methods to win a battle - and no other main game in the series tried to execute this proposal in the same way.

The non-linear progression formula and the move away from the automatic leveling were reused in Final Fantasy VIII, where the Junction system transformed Summons into equipment and spells were linked to increasing attributes, while levels were a compass to define the power of your enemies.

Final Fantasy X also seeks to exercise this proposal, but only in the later stages of the game, where characters can open new spaces on the Sphere Grid to take on new roles, but it also takes another element from FFII when each battle involves strategically choosing the party and switching between them so that everyone gain experience, or to end the fight as soon as possible.

Final Fantasy II - Is It Worth Playing?

Final Fantasy II has a unique space and has become something of a black sheep in the series due to how much it deviates from the standard established in later games.

Its uniqueness is its biggest attraction, as it forces even those most accustomed to the franchise to adapt to this title and its story, which, despite being cliché and short, manages to maintain the pace and engagement from start to finish.

It also features some of the main thematic or mechanical pillars found in later games, such as the unified MP system and the first appearance of recurring elements such as Chocobos, Cid and Ultima.

If you intend to play it, I don't recommend the original NES version, as like the first game in the franchise, Final Fantasy II has bugs and its leveling system is poorly optimized in this version.

The first time I played it, in the PlayStation version of the Final Fantasy Origins collection, my experience with this title was so bad to the point of never playing again after beating it for the first time. After 16 years, I gave it a new chance in the Pixel Remaster version, and the mix of experience gained over the years, fidelity to the original game and interest in the evolution of the Final Fantasy franchise made me appreciate this title much more in 2024 than in 2008.

Conclusion

We have reached the end of the second review in the series.

Final Fantasy II is a recommended game for all fans of the franchise and for anyone looking for a challenge outside the traditional formula of several classic RPGs, but it is also a title that will not please everyone's tastes, and it's okay to feel that this game it wasn't made for you.

Thanks for reading!

— 코멘트 0

, 반응 1

첫 댓글을 남겨보세요